Imagine if you will a world in which D.C. is corrupt. An election of an unsuspected candidate brings the promise of sweeping out the corruption. And someone tries to shoot him.

Something about this feels familiar.

If you haven’t watched the Netflix miniseries, Death By Lightning, you’ll find an obscure story brought to life that, while taking place a century and a half ago, seems to echo our decade. Only, with a twist. The story isn’t just about a U.S. election that took place in the late 1800s. It also feels oddly like it’s taking place in a parallel dimension. Some say history repeats itself. Well, it doesn’t. But it does harmonize.

If you haven’t watched the Netflix miniseries, Death By Lightning, you’ll find an obscure story brought to life that, while taking place a century and a half ago, seems to echo our decade. Only, with a twist. The story isn’t just about a U.S. election that took place in the late 1800s. It also feels oddly like it’s taking place in a parallel dimension. Some say history repeats itself. Well, it doesn’t. But it does harmonize.

In 1881, it was well known that D.C. had become a political machine feeding off of taxpayers. Money was being funneled to men who bribed politicians for made up positions that took a salary for doing next to nothing. The Republican party had celebrated victory since Lincoln, but had also coasted on being the party of Lincoln, and needed new leadership.

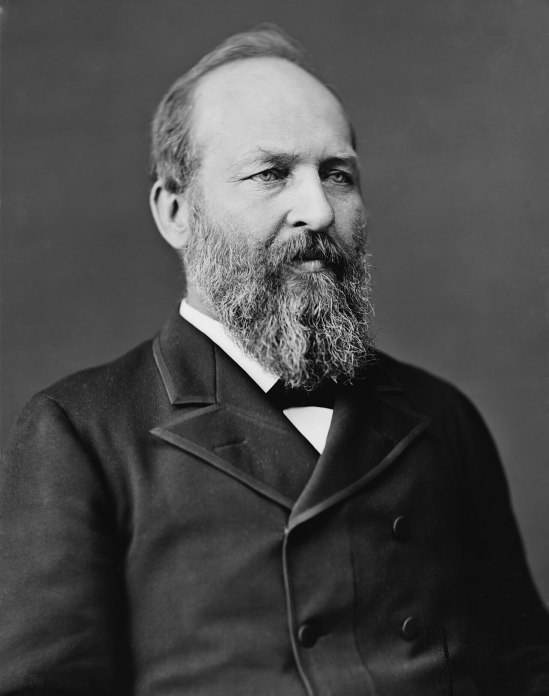

We might expect a charismatic figure to step in and sweep out the rubble. We might have an idea of how he’ll behave. What we get is James A. Garfield.

As we’re introduced to who Garfield is, we get a taste of something a growing number of modern Republicans long for: a president with selflessness and conviction. Garfield spoke against corruption in Washington. But he himself had no designs on the seat of President. In fact, it wasn’t until he made a speech in support of another candidate in the primaries that he begins to look like a good choice. He has a simple life on a farm, he’s not rich, and he’s married to…his first wife. He also served in the Civil War rather than, say, dodge the draft.

When Garfield accepts his nomination and election, the time comes to appoint positions in his administration. He’s swamped with unqualified people who lick his boots for a spot, and—get this—he doesn’t give these unqualified people positions in his administration. Rather than replace one kind of corruption with another, this president actually fights the system. And it makes him unpopular. People are outraged that he “closes the door” on desperate kisser-uppers. Including a severely unhinged grifter.

It would be this man who becomes so enraged by what he feels is betrayal, that he decides to shoot the president. And while this man expects fame, he is soon forgotten. The president succumbs to his wounds, in part because a prejudiced doctor ignores science.

The brief term of James A. Garfield presents to us a kind of blueprint for modern Republicans for what a president fighting corruption should look like. He’s not out to serve himself, but to uplift others. When he says he fights corruption, he doesn’t turn around and bring in more corruption. When people come to him praising his greatness, he tells them they’re mistaken and gives them the gift of humility. In Garfield’s world, opportunists off their rocker are not rewarded, but chastised. Nutballs are not to be given attention. Attention should not be sought after. Bribery will not be tolerated. A man of character must endure. Oh, and maybe staff the Whitehouse with doctors who are caught up on the state of medicine.

Sadly, Garfield, who might have turned out to have one of the politically and culturally healthy presidencies, has mostly faded into obscurity. One of a few presidents who died in office very early. The Republican party of today loves to see itself as the party that ended slavery, but has it sat on its haunches and coasted on grift and greed? Have we contributed to an atmosphere of pleaders and payers? Do we cater to wild wannabe assassins? Do we ignore sound methods of treatment for the dumbest reasons imaginable?

Is a person of true character in a position of power as likely as a strike of lightning?